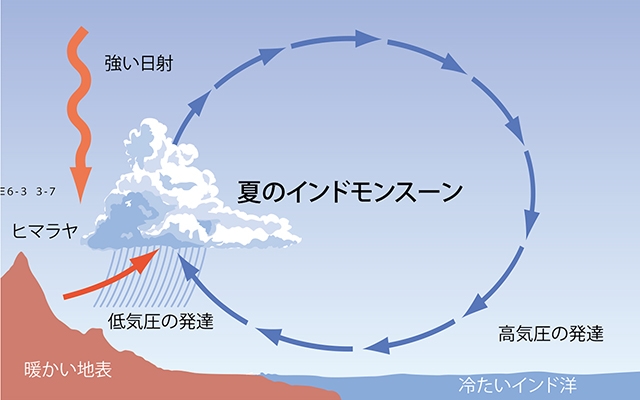

夏のインドモンスーン

Summer monsoon

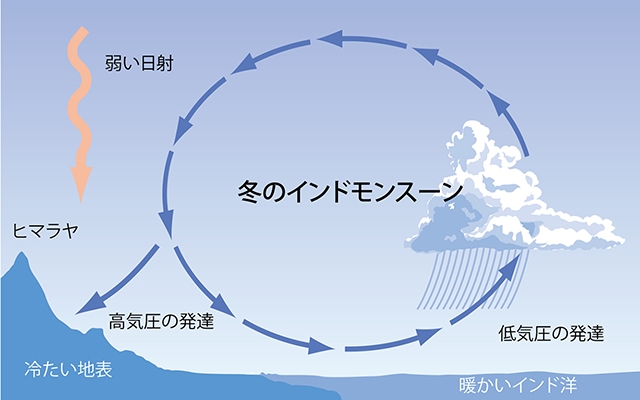

冬のインドモンスーン

Winter monsoon

ヒマラヤ山脈とモンスーン

標高7000〜8000m級の山々が連なる世界最高峰のヒマラヤ山脈。その北に隣り合う平均標高が4000mを越える世界最大規模のチベット高原。これらの「世界の屋根」は新生代のプレート運動(参考☞E1_6)によって造られた。ここでは、ヒマラヤ・チベット山塊の形成に伴う地球環境の変化を見てゆこう。

現在、ヒマラヤ・チベット山塊の南方に隣接するインド亜大陸は、もともとはアフリカ大陸や南極大陸、マダガスカル島などに隣接して超大陸パンゲア(☞E2_6)の南部を構成していた。しかし、古生代/中生代境界にスーパープルームの上昇に伴ってパンゲアの分裂が始まると(☞E2_7)、インド亜大陸は周辺の大陸から孤立して北上し(大陸移動)、赤道を越え、5000〜4000万年ほど前にはユーラシア大陸に衝突した。インド亜大陸はユーラシア大陸の下に潜り込み、その影響で地殻が隆起してヒマラヤ山脈やチベット高原が形成されたのである(参考☞E1_6)。ヒマラヤ山脈とチベット高原は現在も上昇を続けている。

ヒマラヤ・チベット山塊が上昇する過程では、地殻を構成していた膨大な量の岩石がけずられて化学的に変質する(化学的風化と呼ぶ)。岩石の化学風化には二酸化炭素が用いられる。そのためヒマラヤ・チベット山塊の上昇は、岩石の化学風化を通して二酸化炭素(温室効果ガス)を大気から取り除く役割をはたしてきたのである。このことは、新生代の中頃から現在まで長らく続く気候の寒冷化を引き起こす原因となった。

ヒマラヤ・チベット山塊の上昇による影響は、寒冷化だけではない。ヒマラヤ・チベット山塊は生物の分布を制限する障壁となる。また、ヒマラヤ・チベット山塊の上昇に伴ってアジアの広大な地域にモンスーン(夏と冬で風向が逆転する季節風)が吹き始めた。平均標高の高いヒマラヤ・チベット山塊では、夏には大気が暖められて巨大な低気圧が発達し、そこにむかって海から湿った風が吹き込む。反対に冬には大気は冷やされて高気圧が発達し、そこから海洋に向かって乾燥した風が吹く。モンスーンは雨期と乾期の差を生み出す気候システムなのである。そのため、新生代におけるモンスーン気候の発達は生物の進化にも大きな影響を与えてきた可能性が高い。現在、海や湖の堆積物を用いたモンスーン変動の研究が盛んに行われている(☞4ページ)。

The world's highest mountains belong to the Himalayas mountain range with some mountains ranging from 7000 to 8000m in altitude. At the north of the Himalayas mountain range lies the largest plateau in the world called the Tibetan plateau with an average altitude exceeding the 4000m. This "roof of the world" formed during the Cenozoic's plates movement (see ☞E1_6). Let's see the global environment changes that accompanied the formation of the Himalayas mountain range.

Currently, the Indian subcontinent which lies at the southern part of the Himalayas mountain range was originally part of Pangea's southern region (☞ E2_6) and adjacent to the African continent, Antarctica and Madagascar. However, when Pangea started to split around the Paleozoic/Mesozoic boundary because of the rise of a superplume (☞E2_7), the Indian subcontinent found itself isolated from the rest of the continent and started to move northward (continental migration), beyond equator and collided with the Eurasian continent about 50~40 million years ago. The Indian subcontinent sank under the Eurasian continent by subduction and, as a result, the crust rose and formed the Himalayas and Tibetan plateau (reference ☞E1_6). Even nowadays, the Himalayas and the Tibetan plateau are still rising.

In the process of the Himalayas-Tibetan plateau formation, a huge amount of rock that constituted the crust was grinded and chemically altered (also called chemical weathering). The carbon dioxide is used during the rock chemical weathering process. Therefore, the formation of the Himalaya mountain range removed a lot of carbon dioxide (greenhouse gas) from the atmosphere through chemical weathering of the rock. This is the cause of the long-lasting cool climate that happened from the middle of the Cenozoic to the present days.

But the impact of the rise of the Himalaya is not only limited to the climate. Indeed, the Himalaya mountain range became a natural barrier and limited the distribution of the living organisms. The formation of the Himalayas had also some repercussion on the monsoon (seasonal reversing wind in winter and summer) that began to blow in the vast areas of Asia. In the Himalaya mountain range where the average altitude is high, the atmosphere is warmed up in the summer, the air above it expands and an area of low pressure develops. This difference in pressure causes sea breezes to blow from the ocean to the land, bringing moist air inland. On the contrary, the atmosphere is cooled down during the winter season and as high pressure develops, a dry wind blows towards the ocean. The monsoon is a climate system that settles a rainy season and a dry season. Therefore, the development of the monsoon climate in the Cenozoic is likely to have had a major influence on the evolution of living things. Currently, researches on monsoon variation using ocean and lake's sediments are actively conducted (☞ page 4).